Study Bay Coursework Assignment Writing Help

Skin-to-Skin Contact as a Non-pharmacological Treatment for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

This assignment is based on my experience of caring for an infant with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) in a Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU). NAS is a set of signs and symptoms experienced by certain infants after a sudden withdrawal of passively transferred intrauterine opioids or other psychoactive substances used by mother during pregnancy (Gomez-Pomar et al, 2018). Most commonly, these babies demonstrate the following: tremors, hyperirritability, excessive crying, loose stools, vomiting, poor sleeping, yawning, myoclonic jerks, and seizures in severe cases (Wexelblatt et al, 2018). Using the 5Rs Framework for Reflection, this assignment will focus on skin-to-skin contact (SSC) as a non-pharmacological intervention for NAS. SSC involves direct touch by placing a naked infant to a mother’s bare chest (Feldman-Winter et al, 2016). To protect patient confidentiality, the neonate under discussion will be referred to as Star (NMC, 2018).

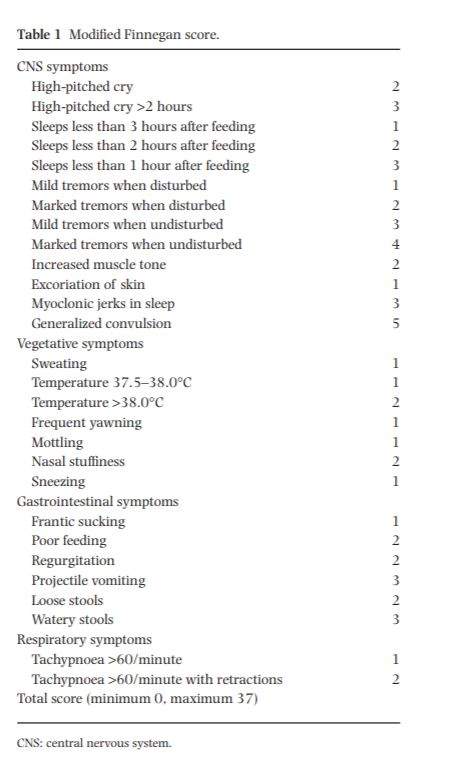

Star was born at 38 weeks gestation and admitted to SCBU. Star’s mother had used 7 different prohibited substances during pregnancy. Both her parents abused drugs and had visiting restrictions due to continued substance use and aggressive behaviour. Star initially received 170 mcg of oral morphine 4 hourly but was weaned to 150 mcg that day. Using the Modified Finnegan Scoring System (see Appendix), Star’s withdrawal scores were graded an hour after each dose. At the beginning of my shift, Star’s withdrawal score was 8 with symptoms including inconsolability, high-pitched cry, sweating and loose stools. I gave another dose of oral morphine but she remained agitated with a withdrawal score of 7 an hour after. A few hours later, Star’s mom came to visit. She appeared calm and appropriate and showed acceptable behaviour. I encouraged her to at least do cares and SSC but she was reluctant. Moreover, a 1-hour restricted visit was not enough for mother to bond with baby and to provide the best care she needs.

The main challenge of the situation was the inability of Star’s mother to provide infant supportive measures due to time constraints and social issues. Thus, not only was SSC unlikely to be provided but, maternal-infant attachment was clearly compromised. This led me to ponder on the nurses’ role in strengthening this bond and in the care for NAS babies without maternal presence.

The post-natal period is crucial for infants in establishing connection to a primary caregiver, which can have long-standing impacts on emotional regulation and attachment patterns (Bystrova et al, 2009). According to Canfield et al (2017), although current health and social policy generally recognise the significance of primary attachment relationship to the infant’s health and well-being, the reality is many substance-exposed infants have limited to no interaction with their biological mothers while hospitalised. The reasons for this lack of interaction may include poor maternal physical or mental health, issues of addiction and, most commonly, the intervention of child protection services.

As for Star’s case, attachment was not facilitated because of mother’s sporadic visits and unwillingness to participate. When mothers do not actively partake and visit their newborns, nurses must ensure they incorporate a caregiving role (Velez et al, 2008). Although many aspects of care must be done by a trained nurse, there are also many tasks that mothers could accomplish to develop attachment. Thus, it is important for nurses to support mothers in fully establishing their role by including them in such tasks when possible so they can contribute to their child’s care in meaningful ways (Cleveland et al, 2013). Promoting maternal-infant connection by engaging mothers with addiction in the care of their infants is one of the most effective ways to improve outcomes for this population (Pajulo et al, 2001). Providing opportunities for mothers to care for their babies is essential to maintain family-centred care.

Non-pharmacologic care of substance-exposed newborns involves performing a thorough assessment of the infant and his mother, providing interventions towards reducing environmental stimuli and promoting social integration for better neuro-developmental and physiologic outcomes (Velez, et al 2008). “An essential component of non-pharmacologic care is the education and facilitation of maternal involvement with the infant” (Velez, et al 2008, pp.113).

One way to encourage a mother’s involvement in her infant’s care can be through simple bedside non-pharmacologic measures such as SSC. Numerous studies have proven the effectiveness of SSC in improving physiologic stability in infants (Feldman-Winter, et al 2016). Through an evidenced-based project, Hiles (2011) found improvements in sleep after mothers implemented skin-to-skin care to NAS infants 1 hour post-feeding (cited in Maguire, 2014). A skin-to-skin/cuddling initiative, part of a coordinated rooming-in model and environmental controls of care described by Holmes (2016), found a 41% reduction in the proportion of opioid-exposed infants treated pharmacologically. A similar, multifaceted model of supportive care initiated with a cohort of 287 NAS neonates described by Grossman (2015) resulted in a decrease in length of stay and need for pharmacological treatment. Interestingly, non-pharmacological interventions were viewed as equivalent to medications; when increased intervention was required, parental involvement was increased. In a retrospective cohort study, Abrahams et al (2007) also found that avoiding separation, particularly in the crucial 4-6 weeks of life, promoted a strengthened mother-infant bond resulting to fewer withdrawal symptoms and required fewer treatment interventions for the newborn. Encouraging mothers to touch, hold, talk to and look at their babies not only has positive effects upon the recovery time of infants with NAS, it also improves the infant’s responses to sensory stimuli (Kenner et al, 2000).

Although the above evidences show that SSC can be a helpful intervention, there is limited study of it on its own, but rather a part of the entire non-pharmacological management to treat NAS alongside with medication therapy. Nevertheless, SSC is convenient, non-invasive and readily available if the mother is involved with care. However, in some inevitable situations like Star’s, I have learned how vital it is for nurses to provide a holistic day-to-day care to babies with absent biological mothers. Murphy-Oikonen et al (2009) advise the requirement for specialist and sensitive training programs for nurses caring for infants with NAS. Furthermore, Kraynek et al (2012) recommend the use of volunteer ‘baby cuddlers’ to reduce symptoms and length of hospital stay in substance-exposed infants. These volunteers provide human contact and comfort by holding, rocking, and soothing the infant. The Developmental Care Team within my unit has just introduced a new incentive where volunteers provide cuddles to babies whose parents are not actively involved in care. Indeed, such supportive touch will be beneficial rather than relying solely on pharmacological interventions which involve more potential risks to the neonate.

REFERENCES:

- Abrahams, R.R., Kelly S.A., Payne, S., Thiessen, P.N., Mackintosh, J. and Janssen P. (2007) ‘Rooming-in compared with standard care for newborns of mothers using methadone’, Canadian Family Physician, 53 (1), 1722-1730.

- Bystrova, K., Ivanova, V., Edhborg, M., Matthiesen, A., Ransjö-Arvidson, A., Mukhamedrakhimov, R.,

- Uvnäs‐Moberg, K. and Widström, A. (2009) ‘Early contact versus separation: effects on mother-infant interaction one year later’, Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 36(2) pp. 97-109.

- Canfield, M., Radcliffe, P., Marlow, S., Boreham, M., Gilchrist, G. (2017) ‘Maternal substance use and child protection: a rapid evidence assessment of factors associated with loss of child care’, Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, pp. 11–27.

- Cleveland, L., and Gill, S. (2013) ‘Try not to judge: Mothers of Substance-exposed Infants’, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 38(4) pp.200-205.

- Feldman-Winter, L. and Goldsmith, J. (2016) ‘Safe Sleep and Skin-to-Skin Care in the Neonatal Period for Healthy Term Newborns’,Pediatrics, 138(3), pp.e1-e10.

- Gomez-Pomar, E. and Finnegan, L. (2018) ‘The Epidemic of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, Historical References of Its’ Origins, Assessment, and Management’, Frontiers in Pediatrics, 33(6), pp. 1-8.

- Grossman, M., Berkwitt, A., Osborn, R., Xu, Y., Esserman, D., Shapiro, E. and Bizzarro, M. (2017) ’An Initiative to Improve the Quality of Care of Infants With Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome’, Pediatrics, 139(6), pp.e1-e8.

- Holmes, A., Atwood, E., Whalen, B., Beliveau, J., Jarvis, J.D., Matulis, C., and Ralston, S. (2017) ‘Rooming-in To Treat Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Improved Family-Centered Care At Lower Cost’, Pediatrics, 137(6), pp.e1–e9.

- Kenner, C., Dreyer, L., and Amlung, S (2000) ‘Identification and care of substance-dependent neonates’, Journal of Infusion Nursing, 23 (2), pp. 105-111.

- Kraynek, M.C., Patterson, M., and Westbrook, C. (2012) ‘Baby cuddlers make a difference’, Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 41 (1), pp.S45–S45.

- Maguire, D. (2014). ‘Care of the infant with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Strength of Evidence’, Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 28(3), pp. 204-211.

- Murphy-Oikonen, J., Brownlee, K., Montelpare, W., and Gerlach, K. (2010) ‘The experiences of NICU nurses in caring for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome’, Neonatal Network, 29 (5), pp. 307-313.

- Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) The Code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council. NMC.

- O’Grady, M., Hopewell, J., and White, M. (2009) ‘Management of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: a national survey and review of practice’, Archives of Disease in Childhood- Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 94(4), pp.f249-252.

- Pajulo, M., Savonlahti, E., Sourander, A., Ahlqvist, S., Helenius, H., and Piha, J. (2001) ‘An Early Report on the mother-baby interactive capacity of substance-abusing mothers’, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 20(2), pp. 143-151.

- Velez, M. and Jansson, L. (2008) ‘The Opioid dependent mother and newborn dyad: nonpharmacologic care’, Journal of Addiction Medicine, 2(3), pp. 113–120. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e31817e6105

- Wexelblatt, S., McAllister, J., Nathan, A., and Hall, E. (2018) ‘Opioid Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: An Overview’, Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 103 (6), pp. 979-981.

- Zimmerman-Baer, U., Nötzli, U., Rentsch, K. and Bucher, H. (2010) ‘Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System: normal values for first 3 days and weeks 5–6 in non-addicted infants’, Addiction, (105), pp.524-528, table.

Appendix

The Finnegan Scoring System, which relies upon discrete nursing observations, is a widely used tool in current practice to assess the condition of a newborn with NAS (O’Grady et al, 2009). Our unit has adopted the use of a Modified Finnegan Scoring System to examine the efficiency of the medical management. Scores above 8 suggest neonatal withdrawal that can be managed with non-pharmacological treatment while scores above 9 on at least two occasions indicate the urgent need to start medication therapy (Zimmerman-Baer et al, 2010). The table below shows the different signs and symptoms of NAS with corresponding scores and the total is then obtained as the final withdrawal score (Zimmerman-Baer et al, 2010).