Study Bay Coursework Assignment Writing Help

Aims: The session aims to introduce students to current issues in river assessment methods and explore turbulence as practical and effective solution to link fluvial processes with aquatic biota.

Intended learning outcomes: By the end of the session, students will be able to:

- Understand the current issues in assessing hydromorphological condition of rivers;

- Understand the two ways of interaction between hydrodynamics and aquatic biota;

- Explore the benefits and challenges to integrate turbulence in the current river assessment methods.

|

Time (minutes) |

Tutor activity |

Student activity |

Aids/Resources |

|

0-1 |

From poor to excellent river conditions |

Watch the video |

video |

|

1-2 |

(Introduction) GT introduces topic |

Plenary |

PPT slide |

|

2-5 |

Participants to identify bad and good factors to evaluate the current status of rivers |

Quiz |

|

|

5-6 |

GT present the current variables to assess river condition |

Plenary |

PPT slide |

|

6-8 |

Video of turbulence + Questions to tutor |

Students watch the video (create a question) |

Slide (questions written by students) + video |

|

8-10 |

GT presents turbulence concepts |

Plenary |

PPT slide |

|

10-12 |

Pairs to come up with the 2 benefits and 2 challenges to integrate turbulence in river assessment |

Write on post-it notes |

Post its |

|

12-13 |

Pairs to stick the post its on the poster |

||

|

13-15 |

Conclusion |

||

|

Formal/informal assessment task |

Answering to quiz result of bad/good factors to predict an effective assessment and answering question to benefits and challenges. |

||

|

Consolidation following the session |

Tutor to send slides. Tutor explains problem/solution to students for review. |

||

Analysis of session plan

The focus of this session is to highlight the need to update the current river assessment adopted by Environment Agency to provide a valid and effective Assessment of fluvial ecosystems (Voulvoulis et al., 2017) to adapt to change in climate conditions. Students are academics and teaching Helpants and already acquired basic principles of fluvial processes from previous backgrounds and life experiences. This would provide insights on how to integrate better predictors (e.g. turbulence) to tackle environmental issues.

The selected learning outcomes provide a potential development of learning new skills through the application of active learning strategies to improve student’s performance and engagement (Freeman et al., 2014). To achieve the outcomes, participants work on basic skills to remembering, understanding and then applying (Anderson et al., 2001) to come up with basic assumptions of why hydrodynamics would affect habitat used by fish and which challenges and benefits the current methodology in river assessment are facing.

To introduce the topic to participants and help them to joined the subject, the session starts with the video of the status of river ecosystems from poor to excellent conditions. Van Kesteren et al (2014) demonstrated the effectiveness of pre-existing concepts in undergraduate students to improve their academic performance by increasing brain connectivity. By encoding brain communications with student’s exam scores, the research highlights the importance of prior knowledge to facilitate the acquisition and activation of memory that improves learning. Although the challenges to connect the neuroscience with education, this finding is in line with Bransford and Johnson (1972) that is relatively old but provide further evidence of the impact of activated knowledge in facilitate comprehension and memorise new information.

Overall, more than 50% of the session uses active learning to ensure students actively engaged with the material of the plan and interact to start to gain knowledge. Following the constructivism theory, the student acts as the main character of the play to construct the concept from experience using interactive technology with autonomy (Bada et al., 2015). The collaboration among learners is also important and provide a social knowledge reflecting the interaction between the task, instructor, and learners. To develop this, students work in pair to solve simple problem-based learning because of time constraint. The discussion between learners and the problem-solving activity reflects a good practice to evaluate current issues and enhance student capacity to research a new approach and work in pair (Powell et al ., 2008). As suggested the four cases analysed by Powell et al., (2008), the problem-solving learning reveals excellent impacts in student’s engagement and ability to resolve practical problems. The active learning techniques are then alternate with traditional lecturing using power-point slides to guide students to new concepts and produce an analysis of the benefits and challenges of hydrodynamics integration to river assessment. Active learning aims to apply different teaching strategies to promote students focus and engagement and to stimulate effectively learning process (Anderson et al., 2001), although testing student progress would be challenging compared to the traditional techniques. To address this, I tailor the session with a couple of informal assessment tasks to be sure all the students elaborate analysis and act of making knowledge meaningful. Following this, a quiz is used to ask students to remember and self-reflect of environmental issues. There are three simple questions and students have 2 minutes to answer due to limited time then I make some observations and present the correct answers. A simple survey of their understanding of river health could enhance student learning and long-term retention together with self-Assessment of what students have understood and what the teacher should revise (Dunlosky et al., 2013). In addition, a second video introduces a new concept to encourage questions from students to the tutor to generate their own action and increase their performance and enthusiasm.

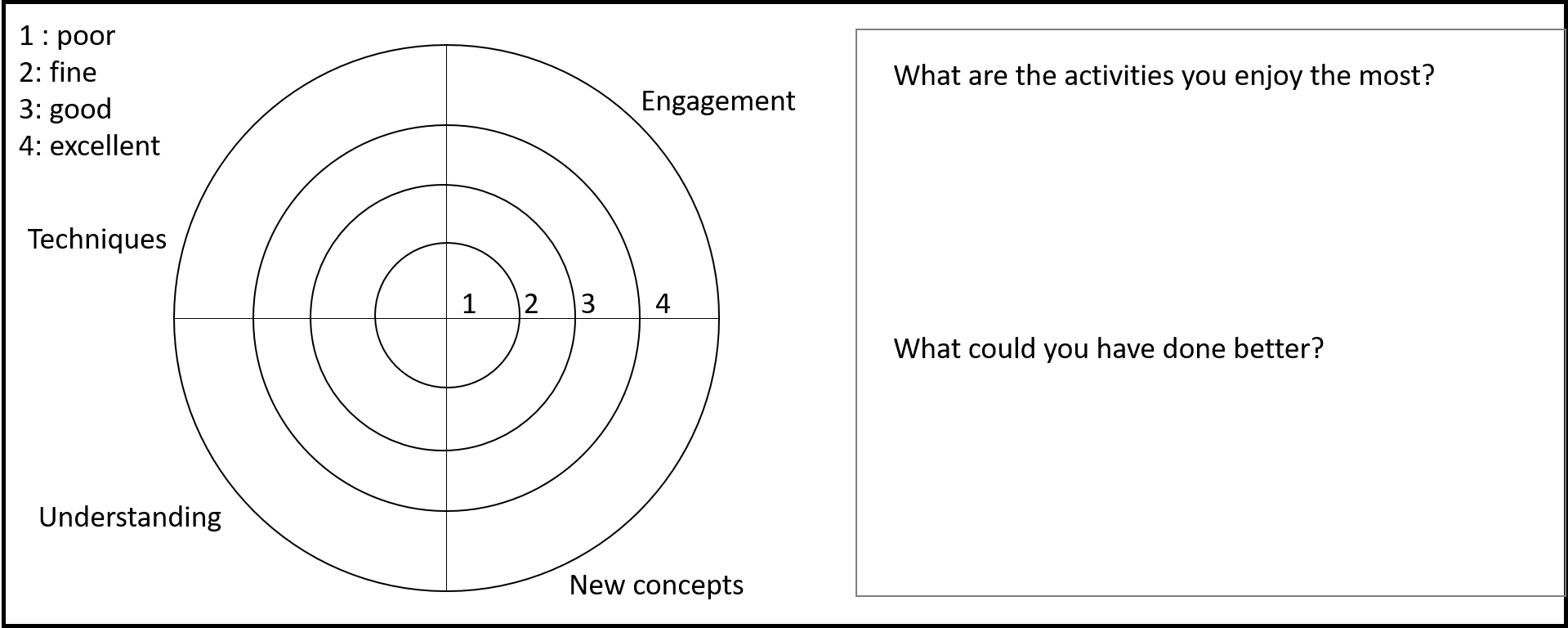

There might be few issues to address during the session. The first potential problems might reflect the time management of the session. As the multiple active learning requires changing activities, the time could be tight and some delays are possible. To tackle this problem, there is an accurate preparation to make sure the visual aids are ready and avoid any digital/electronic interruptions. The second possible difficulty might be the participation of students and the interactions between students and the tutor. The tutor provides support and help to encourage a good social environment and acts as an aware observer during the activity and if needed, he guides students to the tailored expectations. A final Assessment of the session from both students and teacher is helpful to summarise the successes or failures. A brief Assessment provides evidence of positive and negative practices to improve the tutor’s development. Feedbacks from students provide effective assessment whether the activity has been understood and the learning outcomes have been tailored strategically. An adaptation of the learning wheel is used to assess what students have gained at the end of the session in term of new concepts, practical skills and their participation and engagement (Figure1).

Figure 1. This is the brief Assessment to give to students at the end of the session.

For a longer session, a problem based learning using a real case study would be suitable to enhance student’s problem solving. Groups of four or five students might be better to emphasise the importance of the problems and enhance the team working skills.

To conclude, the session reflects a combination of active strategies to activate student’s prior knowledge to be ready to engage with new concepts and use their problem solving in evaluating these environmental issues.

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P., & Wittrock, M. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy. New York. Longman Publishing. Artz, AF, & Armour-Thomas, E. (1992). Development of a cognitive-metacognitive framework for protocol analysis of mathematical problem solving in small groups. Cognition and Instruction, 9(2), 137-175.

Bada, S. O., & Olusegun, S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66-70.

Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: some investigations of comprehension and recall. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 11, 717–726.

Brod, G., Werkle-Bergner, M., & Shing, Y. L. (2013). The influence of prior knowledge on memory: a developmental cognitive neuroscience perspective. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 7, 139.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Hailikari, T., Katajavuori, N., & Lindblom-Ylanne, S. (2008). The Relevance of Prior Knowledge in Learning and Instructional Design. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(5), 113.

Powell, N. J., Hicks, P. J., Truscott, W. S., Green, P. R., Peaker, A. R., Renfrew, A., & Canavan, B. (2008). Four case studies of adapting enquiry-based learning (EBL) in electrical and electronic engineering. International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education, 45(2), 121-130.

Van Kesteren, M. T., Rijpkema, M., Ruiter, D. J., Morris, R. G., & Fernández, G. (2014). Building on prior knowledge: schema-dependent encoding processes relate to academic performance. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26(10), 2250-2261.

Voulvoulis, N., Arpon, K. D., & Giakoumnis, T. (2017). The EU Water Framework Directive: From great expectations to problems with implementation. Science of the Total Environment, 575, 358-366.